by Rosemary Sulllivan

Paris Evening 1934

We were staying at the Warwick Hotel at the corner of Sixth Avenue and 54th, a charming old hotel built in 1926 by William Randolph Hearst for his Hollywood friends whose photos now cover the stairwells and hallways. It was mid-December, on the lip of Christmas, and the city was in a festive mood. I had arranged to meet Peter Stein and his wife Dawn Freer for lunch. Stein is a cinematographer. He has shot over 50 films, T.V. movies, and documentaries and teaches at the Graduate Film School of NYU. His wife is an editor and scriptwriter. But we weren’t getting together to talk about film. We were meeting to talk about Peter’s father.

Peter had contacted me by email to say he had read my book Villa Air-Bel: World War II, Escape and a House in Marseille. The book filled in the holes in his father’s story, a story that they had never really talked much about before his father’s death in 1967 at the age of fifty-eight. Peter said he now understood what his father had gone through as he escaped from Nazi occupied Europe in 1941. If only I had written the book when his father was alive.

Peter asked me if it bothered me when people wrote to inquire about a book I had written three years ago and had long left behind. I replied that Villa Air-Bel is not the kind of book you leave behind. As people discover it, I continue to get inquiries, especially from people still alive who lived its tragic and yet courageous stories of escape. I always reply to their letters because I know the book’s subject is so much larger than the book itself. Though the book records at least forty stories of dramatic escapes, at its core is a central figure, Varian Fry, a young journalist of thirty-three who led the rescue effort to spirit refugees on the Nazis’ most wanted list out of France at the beginning of World War II. Fry went to Marseilles in August, 1940, as the representative of the New York Emergency Rescue Committee, with three thousand dollars taped to his leg, a suitcase with a summer suit, and a list of two hundred people he was meant to save. He stayed in France thirteen months before he was arrested and expelled by the collaborationist Vichy Government. By that time he had saved over two thousand people, three of whom were Peter Stein’s family: his father Fred Stein, his mother Lilo, and his sister Marion.

I hadn’t found Fred Stein in my research and so discovering him was a shock. He was such a remarkable man. Fred Stein was born in Dresden, Germany, in 1909. He was a law student, first in his class, working as an apprentice at the Court of Justice when Hitler came to power January 30th, 1933. Stein had already begun his dissertation, a study of how the new Socialist Movement was using health insurance taxes to help the poor. The dismissal of Jews from public service was reported in the newspapers and he was called before the Nazi commissar of the “Ortskrankenkasse” (the main health insurance institution) and dismissed from his apprenticeship on June 30th. He was also barred from the library and from the State Prosecutor’s Office, which meant that he couldn’t finish the research for his thesis. The Nazis’ edict against admission to the bar of Jews, “for race and national unreliability,” meant that he would never be allowed to practice law.

Stein had been a political activist from his teenage years, distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets on his bicycle and participating in marches. Soon he joined the Socialist Worker’s Party, a non-Communist splinter group of the Social Democrats. The SS began making inquiries about him in 1933. After the arrest of two close friends, the Steins realized it was urgent to disappear as soon as possible. They married in August of 1933 in the Dresden Registry Office. Claiming to be taking a “honeymoon” trip, they abandoned their apartment on Mozartstrasse near the beautiful Grossen Garten shortly after Harvest Thanksgiving. “The ocean of Swastikas on the last day,” Fred Stein told friends, “made an otherwise difficult departure easier.” They reached Paris on October 7th, joining thousands of other European refugees. Like most, they viewed their exile as temporary.

The Steins had managed to smuggle some wedding money out of Germany when they left on their "honeymoon" and were able to rent an apartment in Montmartre, seven flights up. They joked that they were the “capitalists” among their friends, most of whom lived in cramped quarters or shabby hotels in the ragged arrondissements of the city. In police records the German exiles were identified as SDFs (Sans domicile fixe, no permanent address). Willy Brandt, then a refugee in Norway and a close friend of the Steins, used to stop at their apartment on his way in and out of Germany where he was secretly organizing anti-Nazi resistance.

But the question was always how to make a living in Paris. Fred Stein could not practice law. Though he was proficient in French, there was a ten-year residency requirement before a foreign lawyer was permitted to open a practice. He tried selling insurance, but proved useless as a businessman. Lilo got a job as a cook for a collective of thirty-five people in a toy factory. Forced to do the work of three people, she broke down under the pressure.

Before fleeing Germany, as a joint wedding present the Steins had bought themselves a Leica camera. So far they had developed only three rolls of film. That first year, with the Leica and a small enlarger and the audacity of the displaced, they opened the “Studio Stein” in their apartment. Lilo became Fred’s assistant. In their “showcase” in front of the building, they put Fred’s photograph of Montmartre, the first photograph he took in Paris. In order to attract business, they scoured the newspaper ads for festive events and club meetings, and donated their services free. They sold picture postcards in the streets of photographs Stein made of the tourist sites. Only the small trickle of money they received from family back in Germany kept them going.

To survive as a refugee in Paris was not easy. As Lisa Fittko, a fellow German exile, wrote in her memoir Escape through the Pyrenees: “In order to get through, one had to learn to slip through the cracks and loopholes, using every trick and stratagem to slither out of this labyrinth, which was continually taking on new configurations.” By the mid-1930s, there was the plainly visible Paris and then there was the shadow city, filled with colonies of thousands of refugees from Fascist or Nazi dictatorships, speaking a cacophony of languages.

Initially foreign refugees were well received in Paris. They were allowed into the country without much difficulty and numerous relief committees were set up to aid them. But as their numbers increased, right wing newspapers like Action Française began to refer to them as German invaders who were taking bread out of the mouths of Frenchmen. Anti-Semitism was on the rise. Rumors were spreading that Jewish refugees would seek Hitler’s pardon by spying for him. The last straw was when the refugees began monopolizing the cafés of Montparnasse, which were, after all, intended to be “cosmopolitan, not German.” The right wing press began a xenophobic campaign to demonize foreigners: foreigners were responsible for the economic and social ills of France; they were a threat to public order. They should be interned.

In self-defence, the exiles formed their own communities. Soon the Steins could count Arthur Koestler and Robert Capa among their professional associates. They took in comrades and friends as borders—Capa’s girlfriend Gerda Taro stayed for a time in their apartment. This eased the financial strain but brought other problems—the single bathroom that every one had to use was also their darkroom. Work for most foreigners was illegal and the police sometimes showed up, giving forty-eight hours notice before closing down the workshops of friends who had opened their own businesses. Still, the Steins managed to slip through the cracks. And things were improving in France. The anti-Fascist movement, which supported asylum for refugees, was gaining momentum. Fred Stein began to photograph the mass rallies in Paris calling for social justice and sent his photographs to the newspapers. When the Popular Front government was elected in 1936, German émigrés were finally given work permits. The Steins moved to a large, sky-lit studio in the suburb of Port St. Cloud. For the first time in years they were alone and very happy. Through his newspaper work, Stein had made connections with progressive architects in the suburbs of Paris and was photographing their buildings.

Over their first years of exile, Fred Stein had been turning himself into a remarkable and pioneering photographer. Oskar Barnack, a precision mechanic and industrial designer at the camera company Leitz, had invented the Leica camera in 1925, only eight years earlier. Barnake had intended his invention as a compact camera for landscape photography—for all those German hikers climbing mountains—but Fred Stein saw other possibilities. He turned his camera on the street. Because the Leica was handheld, mobile and quick, he found he could snatch moments out of the stream of ordinary life. Along with a few other photographers, he began to expand the vocabulary of photography.

The photographs Stein took of street life in Paris are not just precise compositions, but resonant narratives. This man, who experienced first hand the violations of his human rights, focused on people in a way that is startling for its quality of intimacy and compassion. “When I pass a man on the street,” he said, “I look for his story.”

His most iconic photograph is called “Paris Evening, 1934.” A couple stands in front of an épicerie. It is just possible to make out the dark edge of the building and the reversed lettering of the sign on the overhang. It is so foggy that the opposite side of the street disappears into vagueness. The couple are dressed in dark, concealing overcoats. The man comforts the woman as she looks down with preoccupied concern; the shadow they cast is as dark as their future. What are they talking about? It is impossible not to project onto the image a drama of loss and parting. Stein has caught an exquisitely delicate moment.

His photograph “Selling Flowers, 1935” is equally eloquent. A young woman gestures to the camera with a bouquet of flowers taken from the wicker basket beside her. She is pregnant and holds a young child in her arms. The misery of poverty is eloquently expressed, yet Stein has caught her tender, inviting smile.

“Embrace, Paris 1934” breaks the heart. In a desolate winter landscape marked by the wheels of long departed cars, under a naked frozen street light, a couple embrace. Their bulky coats make the embrace awkward—they almost collide—yet still you can feel the heat of their touching.

“Three Chairs, Paris 1936” is like a short play by Samuel Beckett. Two wrought iron chairs sit adjacent in a snow-dusted courtyard, while a third chair sits at a slight distance. It is evening, but a light sends shadows over the chairs, which are duplicated in geometric patterns on the grass. One chair is isolated while the two others seem to be communicating. The loneliness of the isolated chair speaks to human isolation.

There is a dark subtext to Stein’s lyrical photographs. No one knew better than Stein and his fellow exiles that Hitler was on the move, spreading the brutal shadow of war closer and closer to France. When Hitler invaded Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938, the European powers accepted his absurd ruse that he was simply adjusting Germany’s legitimate boundaries and had no further territorial ambitions. The exiles knew Hitler was testing Europe’s nerve and waited desperately to see when Europe would fight back. By the summer of 1939, Hitler had set his sights on Poland. To appease the Europeans he invented a pretext for the invasion. On the Fuhrer’s orders, prisoners were taken from German concentration camps, drugged, dressed in Polish uniforms, and shot. The bodies were strewn around a German signal station near the Polish border. On September 1st, 1939, in retaliation for this attack, the German army invaded Poland.

On the 3rd of September, England and France finally declared war on Germany. On September 5th, two days later, a French government decree called for the arrest of all German nationals. Whether they had lived in France for decades, or were refugees who had recently arrived seeking asylum from the new Germany, thousands suddenly found themselves branded “enemy aliens.” Having been granted asylum in France, the German exiles assumed they were being commandeered as prestataires—work soldiers. Fred Stein was among those required to report to the Stade Colomb where the posters still announced the last football games and tennis matches. Before he surrendered himself at the stadium, he managed to arrange Lilo’s evacuation from Paris to Evreux in the northwest of France. With her she took their infant daughter, Marion, who had been born the previous year.

Over several days, it is estimated that between fourteen and eighteen thousand ressortissants de nations enemies were rounded up and isolated in Paris sports arenas and other centers. People were ordered to go to the collection centers and were told to bring forks and knives and two days worth of food. The criblage or screening of pro-Nazi sympathizers, who might prove to be enemy spies, and of anti-Nazi exiles, who had the right of asylum, would be worked out afterwards.

Refugees’ accounts of being rounded up contained the same details. Many were arrested without a chance to get in touch with friends; they were not allowed to bring extra clothes with them; they were herded into a sport’s coliseum or some such civic building where they slept on the ground.

They were then transported to detention camps. Fred Stein was one of fifty men herded onto a “sight-seeing” bus. He remembered the trip though Paris with passers-by waving their encouragement from the sidewalks; they thought the men in the bus were new recruits. Stein was taken to a camp in Blois in the Loire, joining six hundred and fifty men in a circus tent commandeered for their use. They slept on the grass. When rain drenched the tent, they were moved to the village of Villerbon.

In the Villerbon detention camp, corruption was rampant and conditions eased somewhat for prisoners who had managed to bring a bit of money with them. With a few francs, a prisoner could bribe the guards, or even the local peasants, to get decent food or smuggle a wife into camp. Everything had a price: heat, light, dishes, even the spot where one slept. But Stein had used all his money to get Lilo and his daughter out of Paris.

It’s astonishing how quickly human ingenuity reasserts itself even in the midst of disaster. Solidarity in the camp was strong. Stein managed the “library” (with books donated by locals) and the “Sorbonne.” Prisoners, many of them intellectuals and artists, taught courses, though the classes were often interrupted when the commanding lieutenant ordered forced marches. Prisoners were supposed to work for pay in the woods, producing charcoal; their money was invariably stolen by the guards. Stein asked to work as a photographer. A friend who was allowed to visit his pregnant wife in Paris, brought him his Leica, and he began to take photographs.

For the first two months of his internment, Stein heard nothing from his wife. He presumed she was safe in Evreux. But when her letters finally reached him at his camp, he learned that her experience was, if anything, more horrific than his. When she arrived in Evreux, she found she was considered an enemy alien and was told she would be imprisoned if she did not leave within hours.

Lilo was sent to a hospital run by nuns in Saint-Brieuc in Bretagne where she was told not to speak German and was expected to work. Her one-year-old daughter was placed among the hospital’s orphans. But her work permit was soon rescinded and she was confined to the hospital grounds, permitted to leave the hospital only twice a month to go to the local gendarmerie to validate her papers. In the unsanitary conditions of the hospital, her daughter Marion became seriously ill. Lilo was allowed to see her only one hour per day.

Tormented by Lilo’s suffering and terrified by his daughter’s illness, Stein pulled every string he could to get a “furlough” from his camp. Amazingly, he was granted two days leave in Paris to “get his papers in order.” Once in the city, he called on every influential friend he could think of to get his wife and daughter the necessary travel papers to return to Paris. He succeeded, but had to return to camp before he could be reunited with his wife. In February Lilo finally managed an illegal visit to Villerbon where she was smuggled into Fred’s camp at night and, after a few days, smuggled out at dawn. She brought him photographs of his daughter, whom he did not recognize. They wept together. Fred Stein would not see his daughter for a year.

When the Germans invaded Holland on May 10th, 1940, Stein and his fellow internees in Villerbon immediately found themselves designated “prisoners of war.” They were relocated to a camp in Marolles, and then handed over to the British Expeditionary Force in Saint-Nazaire. The British confiscated all cameras and Stein’s Leica and photographs disappeared. But at least he was finally allowed to participate in the fight against the Nazis. Internees were set to building roads and unloading ships, earning 50 cents a day.

Through May and into June, the Nazis advanced ever closer. Stein and his fellow internees saw the roads fill with fleeing refugees—one day a hearse jammed with Belgiums passed the camp. When Paris surrendered on June 10th and the German Wehrmacht goose stepped into the city in long dark columns, Stein panicked. He had no idea what his family might be going through.

The French Army and the British Expeditionary Force entirely collapsed before the German onslaught, and Saint-Nazaire, like Dunkirk, became an evacuation point for British soldiers to get back to England. German internees were barred from getting on the ships. They were told: “England leaves nobody in the lurch.” The French would be evacuating them south by boat. But Stein was not taken in by the lie: “We were absolutely like animals in a cage who know that they will be surrendered to the butcher,” he said. From June 17th to 19th, the prisoners waited with their bundles ready. Their camp was now guarded by bayonet-wielding French soldiers, mainly men too old to fight who were drinking themselves into oblivion on the prisoners’ wine rations. German planes flew over the camp, marking it with smoke signals. Stein expected to be handed over to the Germans at any moment.

On the 19th a French lieutenant came tearing into the camp, shouting: “Messieurs: Les Allemandes son la—debrouillez vous en vitesse, mettez des vetements civil (Gentlemen the Germans are here: escape quickly, wear civilian clothing).” The port which the British had just evacuated was even then being turned into a base of operations for the Kriegsmarine, the German navy.

Prisoners poured out of the camp in all directions like a human flood. With three friends, Stein headed south making it onto the last ferryboat to cross the Loire estuary. In 1946, wanting to reconnect with old friends among his fellow German refugees, at least those who had survived, Stein wrote a collective letter in which he described his escape:

We were free—in no-man’s land. Children played in the streets in the summer sunshine, on the anti-aircraft cannons which stood in the open fields. With us went Poles, Czechs, Canadiens. We slept in the woods, begged for food and drinks and finally hid near a village. We heard rumours that the Nazis had already gone in motorized columns from Nantes to the coast - more to the South - so that it would be too late to get to Spain. In order to find out, I was sent to the village to hear the radio etc. I spoke French well - but we had military documents in which our nationality was said to be “German” - so we preferred not to meet French authorities, who either would think we were 5th column, or because collaborators themselves would denounce us as anti-Nazis. I confided to an intelligent businesswoman - after I had touched her heart with Marion’s picture - and she told us the whereabouts of a hidden hamlet (which had been her home). There we four were accepted by the old peasants (the young ones had been drafted), were fed splendidly - in the whole neighborhood, peasants knew about us and brought butter, rabbits, and other things for our provisions. We helped with the harvest work, hid our things in the woods and slept in the barn. In the meantime the Nazis were all over. I saw them when I rode on a borrowed bicycle to the village (those peasants did not even have a radio)

Stein and his friends were not alone on the route south. Beginning in mid-May, 1940, it is estimated that between six and eight million people abandoned their homes and fled west and south to Toulouse and Marseilles. The highways and fields were filled with the fleeing French army, with Parisians, with refugees from Alsace, Lorraine, Belgium, Holland and scores of other places. This mass migration would be called La Pagaille (the great turmoil). Entire towns became ghost towns overnight. The fields were littered with cars abandoned when they ran out of gas or broke down. They lay like skeletal remains, some burned hulks, others overturned, their wheels spinning. The Germans were bombing the roads to prevent the advance of the French soldiers and to terrorize civilians. Overhead German planes drew circles of vapour in the sky to mark the spots on which to drop the next bomb load. Other planes followed in a leisurely fashion, strafing roads and fields with machine-guns fire to kill any survivors.

Amidst this infernal chaos, Premier Paul Reynaud fled with his government to Bordeaux, where he offered his resignation. It was accepted. On June 17th , the octogenarian general, Marshal Pétain, was voted in as head of the new government and immediately shut down parliament. Stein and his friends heard the rumours that Pétain intended to sign a cease-fire with the Germans. They waited.

On June 22nd, five days later, Hitler accepted the surrender of France. Under the terms of the Armistice, France was divided into occupied and unoccupied zones. More crushing to foreign refugees, under Article 19, Pétain committed his government to “surrender on demand” all German nationals requested for extradition by the Third Reich. Those who had fled to France seeking asylum could expect to be deported back to Germany.

Stein and his party decided to split up. Two of the men headed back to Paris to say goodbye to their girlfriends. Having no idea where Lilo might be, Stein decided to flee with his third friend to the unoccupied zone. To the men’s enduring gratitude, they discovered the peasants had taken up a collection for them, which meant they had a little money. They traded their decent clothing for bleus (a kind of coverall), carrying their utensils in one pocket and a full bottle of wine in the other. The two men tried hitch-hiking, but when they discovered that a truck they had tried to flag down on the highway turned out to be a German truck, they decided to keep to the fields. Many of the villages were still occupied by French soldiers, whom they viewed as being as much of a danger to them as the Germans. They searched for isolated farmhouses, where they always received food and drink, and took to traveling across the fields at night. Soon they decided it was best to travel separately.

Fred Stein was not much safer in the free zone. His name and address, his political affiliations, and his activities at the Antifascist German Kulturkartell were, as he put it, “nicely written down in the Paris police prefect’s office, so the Nazis did not even have to ask me.” In his letter, he describes his journey:

It took me nearly three weeks to go a very short distance because I was in “Free” France. When I - sitting on a horse drawn vehicle - (my feet hurt very much) drove closer and closer to a French flag - the first in quite a long time - I felt insecure and got out of the way instinctively. I still had to do that very often during the following months, because the flags of Mr. Petain now were hung in the detention camps of Vichy - which I escaped with much luck and effort (he even extradited his own citizens to the German camps.) During the flight in the occupied zone, I sent two cards to Lilo in Paris - on June 22 on Lilo’s birthday, and on mine - July 3rd - in case she was there or that somebody could send her the mail. I didn’t know what had happened to her. After I arrived in Southern France I wrote to post offices of unoccupied France, of North Africa, to England, to the USA - asking the relatives there about Lilo and the child. It is said that many friends found each other in this way. There were no newspapers, or if there were - then only from one side. I had gone to Graulhet in Tarn because I knew that years ago a family from Dresden (Lonker) had moved there. I took a chance to see if they were still there. In my last card to Lilo (of course with a wrong sender in case the Gestapo was already interested) I hinted that I would “appear” at those people and that Lilo - if possible - should get in touch with them. (there was often a mail blockade between the two French zones.) On July 8 this card came into the possession of Lilo.

By the time Lilo received his postcard, Fred Stein had moved on to Toulouse. The city was like a disaster zone. It had been designated a center for Belgian and Polish refugees, and the population had quadrupled in a fortnight to about a million. Hotels were so full that people were sleeping on billiard tables, under dining tables and in lobby chairs, or outside in automobiles and on the grass in public parks. Everyone was looking for someone. Advertisements appeared in newspapers searching for lost husbands, wives and children. “Mother seeks baby daughter, age two, lost on the road between Tours and Poitiers in the retreat” or “Generous reward for information leading to the recovery of my son, Jacques, age ten, last seen at Bordeaux, June 17th.” Messages were left on city hall billboards until there were so many they fluttered in trapped flies. Stein found shelter with the socialist mayor of Toulouse. He was given quarters in the chicken house.

For some time Lilo had been trying desperately to get out of Paris. To evacuate by train or highway with a baby was too dangerous because the Germans were targeting both. When a friend suggested an acquaintance would take them through the interior canals on his yacht, Lilo jumped at the chance, but they had only gone a few miles when the French personnel abandoned ship. She returned to Paris only to witness the Nazis march into the city the next day. It was, of course, the Gestapo she most feared.

When Fred’s postcard arrived, it was her first lifeline, but passage into the unoccupied zone was as controlled as at any international checkpoint and to be found crossing the line illegally could be fatal. With a courage one can only imagine, she presented herself to the German Kommandantur.

Proficient in French, she posed as a French national who wished to join her demobilized husband in Toulouse. Astonishingly her performance was so good that the German official didn’t even check her papers, which would have revealed her to be a refugee provenant d’Allemande. She fled the Kommandantur with her safe-conduct pass clutched in trembling fingers. By mid-June she and her daughter arrived safely in Toulouse. She had managed to bring with her a backpack full of Fred Stein’s negatives and prints. They were too valuable to leave behind.

Now that the Steins were reunited as a family, the question was how to get out of France. The French borders were closed. Anyone wishing to leave needed an exit permit from the French government at Vichy.

The only hope left was to make it to Marseilles, the single major port in the Unoccupied Zone. But Marseille itself was in chaos. All that summer, thousands of refugees had poured down the boulevard d’Athènes following the lure of the sea and the illusion of freedom carried on the wind. They settled into the obscure little hotels tucked away in the city’s back alleys and waited.

Then, at the beginning of September, the city of Marseilles passed an ordinance authorizing prefects to intern, without trial, individuals deemed a danger to public safety. On July 8th it was declared that no resident alien was allowed to travel or move from his actual domicile. Soon another ordinance was passed preventing refugees from living in a hotel for more than five days. Many took to renting rooms in bordellos because the police could be bribed to look the other way. The Unoccupied Zone had effectively become a police state.

That summer in Marseilles, crowds of refugees replaced the tourists. Some 190,000 displaced persons had suddenly augmented the city’s population, estimated at 650,000 in 1939. The numbers were staggering. Everyone knew that few ships were sailing, yet the refugees still came to the port. They had nowhere else to go. They sat in taverns like the Bar Mistral and waited for rescue. The refugees lived in constant fear. Rumours travelled through the narrow streets: the Germans were about to occupy Marseilles; to apply for a residency permit was a ticket to a concentration camp; the Gestapo were in Marseilles disguised in civilian dress. The refugees understood that Vichy was cooperating with Hitler.

One hundred and ninety thousand refugees needed to apply to the Préfecture for permis de séjour (temporary residence permits) in order to stay in the city legally. But to get the permits, they needed to prove that they had every intention of leaving; they needed to obtain international visas to another destination. Without these, they could be sent to internment camps. As often as they dared, they took the trolley to a château in Montrédon on the outskirts of Marseilles where the visa office of the U.S. consulate was housed. They might have saved themselves the trip. The signs posted outside the visa office: Applications from Central Europe Closed; Quota Transfers from Paris Discontinued made it clear that the Embassy was issuing few American visas.

Since all newspapers and radio stations had been taken over by the “New Order” at Vichy, the refugees had only rumour to fall back on. By the end of July, one such rumour had solidified into fact. The Vichy government was going to keep to the terms of Article 19 of the armistice to “surrender on demand” all Germans named by the Reich. For these people, it was now imperative to get out of the country, but who was on the Germans’ list and how were they to get out? The Armistice had put all shipping, whether in Occupied or Unoccupied France, under German control and the German navy was patrolling the Mediterranean. The number of ships departing from Marseilles dwindled to almost nothing. Because Portugal remained a neutral country, there were still international sailings from the port of Lisbon, but the paperwork required to get there had multiplied exponentially. One needed a valid passport, a safe-conduct pass to the French border, a French exit permit, a Spanish entrada, Portuguese and Spanish transit visas, and an international overseas visa.

Everyone understood that it would take no time before any of these documents could be bought on the black market—Vichy officials would soon be conducting a brisk trade in exit-permits and even stateless refugees could always buy a forged passport.

But who, except the privileged few, had enough money? It seemed there was only one consolation left. It would take the Vichy government months before they would become efficient enough to round up so many refugees. Soon international aid groups began arriving in Marseille. The American Friends’ Service Committee run by the Quakers under Miss Holbeck; the YMCA under Dr. Lowrie; the Unitarian Service Committee; HICEM, the international Jewish relief agency; the Oeuvres de Secours aux Enfants (OSE), a children’s aid committee; the French Red Cross, the Belgian Red Cross, and the American Red Cross, as well as Russian and Czech organizations. Enough organizations to keep the refugees “prisoners of hope.”

But it seemed there was one man who could help. It was rumoured that an American, Varian Fry, had set up a committee called Centre Américan de Secours or CAS, which could get the required documents. More importantly, for refugees who were too well known to travel legally, Fry organized a secret escape route over the Pyrenees to smuggle them out.

Fred Stein probably heard of Varian Fry on the refugee grapevine. Leaving Lilo with the baby in the chicken shed, he boarded the train for Marseilles to see if there was any truth to the rumours. He was terrified of arrest—what would happen to Lilo and the baby—and hid out during most of the trip in the bathroom, only vacating it when other passengers demanded to use the facilities. French inspectors always patrolled the trains to check identity papers.

In addition to his anti-Nazi associations and activities in Dresden, Stein had been an officer of the Anti-Nazi Journalists’ Association in Paris. He had reason to hope his name might be on Fry’s endangered list. He made his way to CAS’s office at 60 rue Grignan and joined the line of hundreds of men, women, and children waiting patiently on the stairwell. In the room at the top of the stairs, Fred Stein would have found five or six haggard employees engaged in interviewing refugees. The jarring sounds of multiple languages and the smell of shabbily clad people jammed together in an airless space would have been daunting.

But Varian Fry took the Steins under his wing. Since both of the Steins were prohibited from working, their money had run out. Fry’s committee gave them a meagre stipend, a mixed blessing in that it meant their names were kept on a list in the office files. When the police raided the rue Grignan office, some whose names were on the committee’s list ended up in the Camp des Milles internment camp near Aix-en-Provence until the committee took to hiding its lists or using code. “With luck and much effort,” as Stein himself put it, he managed to avoid the detention camps. It took over eight gruelling months of terrified waiting until Fry obtained the Stein family’s international emergency rescue visas to the United States.

On May 6th, 1941 they sailed from Marseilles on board the Winnipeg. After the rigours of incarceration, the long trek, and the food shortages in Toulouse, Fred Stein weighed only 125 pounds. En route to Martinique, the Winnipeg was stopped on the high seas when a boat fired a shot over its bow. All the passengers thought it was a German war vessel, but thankfully, it turned out to be the Dutch Navy. The boat was rerouted to Trinidad in the British West Indies. The Steins were again incarcerated in a British detention camp where the men were separated from the women and children—Lilo and Fred were allowed to meet once a day across barbed wire. But, in comparison to the Winnipeg, the food in the camp was “heavenly” and the conditions were hygienic. Finally, through the intercession of the Jewish Labor Committee and Fry’s Emergency Rescue Committee, the Steins were permitted to continue to the U.S. aboard the SS Evangeline.

The Winnipeg had already been well used as a refugee evacuation ship. In September 1939, the poet Pablo Neruda, then Special Consul for Immigration in Paris, had hired the SS Winnipeg to transport 2,200 Spanish refugees to Chile. The Spaniards had been languishing in French internment camps in the south of France after they had fled over the Pyrenees with 450,000 others, pursued by Franco’s victorious army. Neruda reported that this was “the noblest mission I have ever undertaken.” According to Peter Stein, the accolade of “nobility” also belongs to Varian Fry. Varian Fry saved his father, mother, and sister from what would have been certain deportation and death had they been trapped in France.

The Steins carried little with them as they crossed the ocean, but they managed to save the bulk of Fred Stein’s photographs and negatives. There were a few photographs they considered too dangerous to take with them, such as the photographs of the political rallies; these they sent to an archive in Holland for safekeeping. The archive was later bombed and the pictures were permanently lost.

When they arrived in New York, the Steins did not find life easy. They were poor. Lilo Stein worked first as a floor girl in a curtain factory, then as a seamstress on a power machine, a homeworker putting labels on handkerchiefs, and finally as a photo finisher in various plants. Fred Stein took care of the children as he struggled to find commissions and contacts as a photographer. Still, New York was freedom; it offered the oxygen of personal choice. Not to be controlled by fascist rules. Released from fear, Stein devoured the city, haunting its streets and taking endless photographs, finally able to indulge again a passion that had been brutally stolen from him.

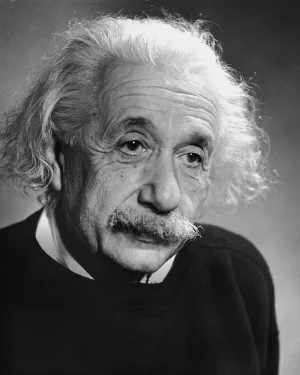

Stein proved a brilliant portraitist. Soon he was photographing everyone, including fellow exiles like Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, and Salvador Dali, and notable Americans like Frank Lloyd Wright and Georgia O'Keeffe. Hanna Arendt, Norman Mailer, and Marc Chagall came to him for portraits.

Fred Stein worked hard as a portraitist. He once remarked that “full recognition of a person is not in the exterior identity alone but elaborated and made convincing by some visible element of individuality. The photographer is alert to attitude, gesture, and expression, and snaps the shutter at the critical moment when these signs all blend together to describe the inner personality.”

Stein’s photograph of Einstein is iconic. Through his refugee connections, he had wangled a ten-minute interview with the great man that turned into a two- hour conversation. Perhaps they talked about the loneliness of exile, which Einstein captured perfectly in his diaries: “Well, then, a bird of passage for the rest of life. Seagulls accompany our ship, constantly in flight. They will come with us to the Azores. They are my new colleagues, although God knows they are happier than I. How dependent man is on external matters. Compared with the mere animal….!I am learning English, but it doesn’t want to stay in my old brain.”

Albert Einstein, Princeton 1946

In Stein’s photograph, Einstein’s head is slightly bowed with the weight of his knowledge and his face is fraught with pain, but the photograph captures his warmth and compassion. In 2005, the German government selected his photograph for its commemorative stamp of Einstein. The stamp feels like an apology for Einstein’s brutal treatment by the Nazis. In 1933, shortly after Hitler came to power, Einstein was dismissed as a Jew from his university post. His Berlin apartment and his summer cottage were raided and sealed. Shaken and dejected, Einstein, then in the U.S. on a lecture tour, renounced his German citizenship. At the age of fifty-four the world’s greatest physicist was suddenly a man without a home or a country.

At the same time as he took portraits, Stein worked on his street photography. New York City’s neighbourhoods, its architecture, and its different socio-economic enclaves fascinated him. He documented street life from Fifth Avenue to Harlem. He became a member of the Photo League until he resigned, disconcerted by its pro-Communist sympathies.

When Stein photographed children, it was mostly in groups. His moving photograph of children in Paris reading a newspaper defined his standard. The children sit on the bare sidewalk, four young children huddled around an older boy who is holding the newspaper. Their concentration is intense. It is likely that only the older boy can read. The younger children lean in. From the seriousness of their faces, the story he is reading them is not a happy one. It is 1936. Perhaps they are reading about the bombings in Spain, caught in the conflagration of a Fascist coup.

But in New York, Stein’s photographs were poignant in a different way. In “Children in Harlem, 1947,” he has caught children playing with abandon in water flowing down the gutter from a broken water main. Their smiles are gleeful, but the viewer knows that the image also expresses their poverty and marginalization.

A photograph called “Italy Surrenders, 1945” is pure Stein. It is not a militarist photo of a victory parade, but a portrait of a family reading a newspaper. This is where history impacts, where history hurts. The newspaper headline facing the viewer reads in bold type: Italy Surrenders. The mother’s smile, half obscured by the newspaper, speaks of joy and relief. Now no one else needs to die. An infant in his carriage sucking on his bottle, oblivious to history, is the central focus in the forefront of the image. He is the future.

Dawn Freer has written exactingly of her father-in-law’s photography: “His work is the document of an exiled European, an intellectually and politically committed man driven out of Germany by the Nazis. Chance made him an outsider, the observer; from this vantage point came his approach and his vision.” Chance also meant that Fred Stein died in 1967 before the wave of interest in documentary photography stormed through New York in the 1970s, securing the fame of photographers like Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bressai and David Seymour (Chim). Fred Stein was a stunning documentary artist. His exile should end. He should now be restored to their company.